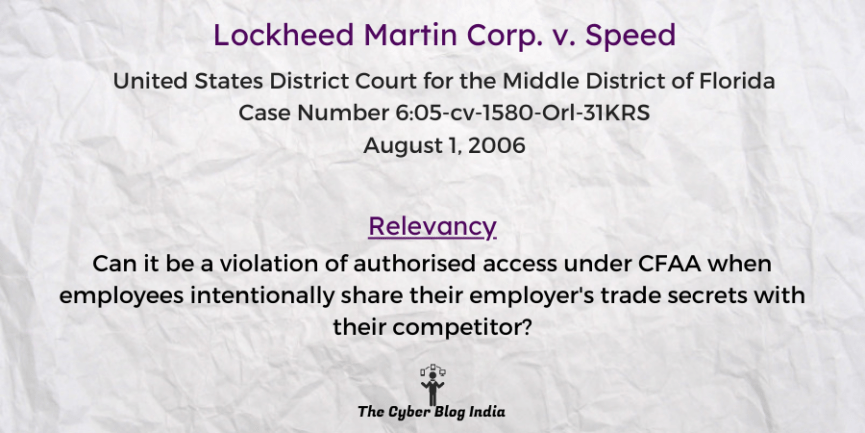

Lockheed Martin Corp. v. Speed

Lockheed Martin Corp. v. Speed

2006 WL 2683058

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida

Case Number 6:05-cv-1580-Orl-31KRS

Before District Judge Gregory Presnell

Decided on August 1, 2006

Relevancy of the case: Can it be a violation of authorised access under CFAA when employees intentionally share their employer’s trade secrets with their competitor?

Statutes and Provisions Involved

- The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1030

Relevant Facts of the Case

- Lockheed Martin, the plaintiff, claims that three of its former employees accessed its computers, copied proprietary information, and delivered the trade secrets to the defendant L-3 Communications Corporation (“L-3”).

- The plaintiff and L-3 are competitors in the defence and aerospace industries. They made competing bids for a United States Air Force (USAF) contract called ATARS I (Aircrew Training and Rehearsal Support).

- USAF eventually awarded the ATARS I contract to the plaintiff in June 2000. The contract is due for termination on September 30, 2006. ATARS II, an extension of ATARS I, is valued at $1 billion. USAF would award the ATARS II contract in the third quarter of 2006.

- The plaintiff alleges that L-3 conspired with three of its former employees, namely Speed, Fleming, and Romain, to gain an unfair advantage in its bid for ATARS II.

- Speed was a program manager during his employment at ATARS I and had the ultimate responsibility for ATARS I. He had complete access to confidential, proprietary, and trade secret information. Before resigning, he copied 200 documents from his work computer by burning them onto a CD. Thereafter, he joined Mediatech, which acted as a hiring front for L-3.

- Fleming was a senior manager during his employment at ATARS I. He had unrestricted access to the company’s shared network drives, including folders containing ATARS I data. He joined L-3 after resigning from the plaintiff’s company. He burned 262 files onto a CD before he left. Moreover, he synchronised 9 files to his BlackBerry personal digital assistant (PDA). On this last working day, he copied 63 files on two CDs, including the most recent and detailed program review.

- Romain was a site manager during his employment at ATARS I. He also had access to confidential, proprietary, and trade secret information and financial, technical, and strategic data related to the ATARI I project. On his last working day, he synchronised data to a Dell PDA and removed them from the work computer.

Prominent Arguments by the Advocates

- The plaintiff’s counsel argued that the loss of trade secrets resulted in additional costs incurred in recovery and conducting a damage assessment. He submitted that the defendant’s interpretation of authorisation is too narrow. The employees access information with an intent to steal and deliver the same to a competitor. They acquired adverse interests and terminated their agency authority subsequently. Therefore, they accessed information without authorisation. The counsel placed reliance on the cases of International Airport Centres LLC v. Jacob Citrin and Shurgard Storage Centers, Inc. v. Safeguard Self Storage, Inc.

- The defendants’ counsel argued they did not access the work computers without authorisation or exceeded authorised access. The plaintiff provided the employees as a function of their respective positions.

Opinion of the Bench

- The plain language of CFAA is sufficient to interpret the terms without authorisation and exceeds authorised access. The court did not favour the interpretation given in the Citrin and Shurgard cases.

- CFAA defines “damage” as any impairment to the integrity or availability of data, program, system, or information. However, the loss of trade secrets does not constitute damage under CFAA. Copying information from a computer onto a CD or PDA is a relatively common function. This act, by itself, does not cause permanent deletion of the original files. The plaintiff did not allege any permanent deletion or removal in their filings.

Final Decision

- The bench granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss while allowing the plaintiff to replead within 20 days.