Big Tech, Politics, and Scandals

When Christopher Wylie was in his mid-teens, he expressed hopes of becoming a statesman. If not, he assumed he would be another small merchant resorting to Machiavellian methods to sell petty goods. A decade later, he finds a place in the list of Time Magazine’s “100 Most Influential People 2018” for blowing the lid on Cambridge Analytica malpractices and making Facebook cough up billions in fines. When asked to testify about the ordeal, he spoke about the risks of big IT companies’ power and of a novel Cold War emerging in the cyber space. In his book Mindf*ck, he says,

Why should we allow Big Tech to conduct scaled human experiments, only to realise that they become too big a problem to manage?

What is Big Tech?

Big Tech refers to the five most prominent IT companies in the US – Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, and Apple. These companies are enormously powerful in the cyber space, and it is impossible to imagine an internet without them. Facebook and Google account for more than 70% of all web traffic. Their popularity continues to soar even after criticism, scandals, data leaks, and anti-trust lawsuits. This is primarily because of their free services and the central role their systems play in our everyday lives.

What is the problem?

Lately, the enormous influence of IT companies has come into increased scrutiny. Data leaks, privacy concerns, and influence in state affairs are factors responsible for this. Limited accountability and wanton disregard for the intellectual property of users simply add fuel to the fire. When predictive analytics were first developed in 1689, they were used on a smaller scale in underwriting to help disseminate important information in insurance services. The growth of social media revolutionized the scale on which these worked. Now, these algorithms can easily predict our conduct with embarrassing accuracy.

They study our behaviour – how much time we spend on a particular site, what we look at, what we like and share, even how long we look at a particular thing. Thus, it collects all sorts of data about us – who we like, what questions we’re asking, whose profile we keep going to, what keeps us up at night, what makes us angry, and what makes us tick.

Can algorithms trick us?

Big Tech companies use predictive analysis for showing ads to the users. These algorithms provide us with personalised ads based on what site we are likely to visit, what page we might like to open, and which product we are more likely to buy. The situation becomes grave, particularly in political ads, since parties can roll out personalised ads for different kinds of people, cherry-picking a certain item in their agenda that one might support. The claim might be misleading or outrightly false. In a U.S. Congress hearing, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez asked Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg about advertising lies as political advertisements. Visibly befuddled, he said, “I don’t know.”

So, a political party with more money can roll out greater ads and influence voters’ decision-making. They can also test how influential a certain advert is by looking at engagement and response data. If one advert is not generating enough engagement, they can change it in real-time. When companies want to, they can also influence people’s behaviour, showing them little by little, the narrative they want them to support. These sites have billions of users and a serious dearth of employees or fact-checkers to decide what the objective truth is and isn’t.

Moreover, companies like Google also have customized news feeds, which show personalized content, often detailing only one side of the story. The algorithm keeps showing people more and more content on views they already support, wiping out debate and discussion and creating personalized echo chambers. Each post thrusts people into binary conflicting sides and feeds on these divisions. On the other hand, it also rewards controversy, as more controversy means more engagement, more ads, and more profit.

Facebook and the Cambridge Analytica Scandal

In 2010, Facebook launched a platform called Open Graph that allowed third-party apps to ask Facebook users for permission to access their personal data. “This is Your Digital Life” was one such app, and it branded itself as a personality quiz. It asked users to answer questions based on their behaviour and psychology. The app claimed that these questions are for academic purpose, and after completing the quiz, it paid the users. The app found a loophole in Facebook that allowed it to obtain the data of users’ friends as well. Subsequently, it shared the collected data of millions of respondents and their friends with Cambridge Analytica. Cambridge Analytica, in turn, used this data to launch targeted political ads on Facebook.

The Ted Cruz Campaign

Cambridge Analytica was established as a subsidiary of the SCL group. Conservative Robert Mercer founded this company on the promise of profiling users and influencing their behaviour. It was a political consulting firm on record, and it started off by helping Ted Cruz in his presidential campaign in 2015-16. With funding and analytical tools available, it did not have the data to make its idea work. It wooed Russian-American Aleksandr Kogan for procuring data, and the data was bought from Kogan’s app (This Is Your Digital Life).

Subsequently, the company started creating psychological profiles for individuals. The ad campaign utilised these profiles to create tailored ads and influence the voters to vote for Cruz. It specifically categorised individuals into categories like “True Believer” and “Stoic Traditionalist.” In late 2015, Facebook became aware of this incident and how data was illegally obtained. Cambridge Analytica responded that they did not know about this and they would destroy it. As this incident started gaining traction, Facebook stopped the ads and removed Cambridge Analytica pages from its platform. Cruz claimed that the data was legally acquired; however, it was unreliable and not worth the money. Later, he dropped out of the presidential race, and the firm began working for Donald Trump.

Trump’s 2016 Presidential Bid

After Cruz’s failed campaign, Cambridge Analytica started working for Donald Trump in his presidential bid. This time, they categorised individuals in broad categories, such as Trump Supports, of if they can be influenced to swing in his favour. For the first category, the ads displayed a triumphant Trump, along with the details of polling booths. For the second category, negative visuals of the rival candidate, Hillary Clinton, were shown along with major Trump supports. In one instance, Politico, a news website, published an interactive graphic that looked like genuine journalism, but it was actually sponsored content and criticised Clinton thoroughly.

One of the ads during the Trump campaign

Brexit

In 2015, the Leave campaign boasted about working with Cambridge Analytica on its website to better engage the voters. The Communications Director of the campaign had recommended the company to others. However, they later denied any involvement and claimed that no paid/unpaid work was done. According to Wylie, the Leave campaign worked with Cambridge Analytica through a third company called Aggregate IQ. Leaked emails between the parties further substantiated this stance. The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) launched an investigation and concluded that Cambridge Analytica was not involved. However, Facebook paid a penalty of £500,000 for not putting in place sufficient safeguards for protecting user data.

The Exposé and Aftermath

In 2017, the true scale of this breach came to light. Carole Cadwalladr, an investigative journalist, convicted Wylie to divulge the working of Cambridge Analytica. A year later, he came forward publically with the allegation of misuse of user data. These allegations set off a series of investigations that demonstrated the true extent of the leak. After significant public outrage in early 2018, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg apologised for the situation and called it a mistake. Facebook entered into a settlement with ICO and FTC and paid a fine of $5 billion. It entered into another settlement with SEC and paid $100 million.

This scandal gained widespread public attention, and the number of likes, comments, and shares on Facebook decreased by almost 20%. Since then, the engagement has continued to decrease. On Twitter, some users started a #DeleteFacebook movement, but it failed to materialise. Another campaign called #OwnYourData was started, and it demanded greater transparency from Facebook. A documentary on this incident called “The Great Hack” is available on Netflix.

The Indian Context

In the last 5-6 years, the number of Internet users in India has increased by at least four-folds. Mobile phones and data packs are cheaper than ever. While this sudden influx of netizens may go a long way in increasing connectivity and modernisation, it leads to rampant fake news. The most common vehicle for rumours to ride on is WhatsApp. Often, YouTube videos become a medium of information that users share on other social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. According to a Hindustan Times report, regional platforms like ShareChat and Helo are equally littered with fake information.

An Oxford study found that India forms a part of the countries where political parties have an organised social media manipulation campaign. A BBC report showed that lines between social media platforms and news sites have been blurred, as there is cynicism about the traditional media agencies and their motivations. Users continue to share unverified information through social media under the impression that it is their civic duty. Often, nationalistic fervour or identity politics drives people to share such messages. This reaffirms people’s identity, and it trumps the authentication of facts. The report further highlighted that the motivation behind sharing fake news is tied up with socio-political identity. To read more on the proliferation of fake news through platforms like WhatsApp, click here.

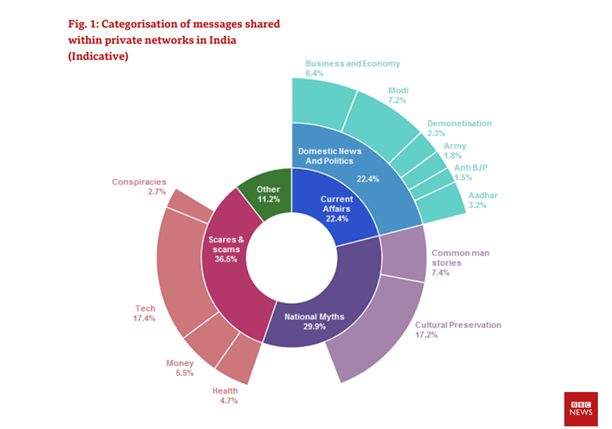

Categorisation of messages shared within private networks in India

2019 Election

In the 2019 General Elections, major political players had extensive plans for social media campaigning, with thousands of individuals assigned for launching campaigns on WhatsApp. The Election Commission had to intervene and frame guidelines that allowed for the scrutinisation of social media posts. It launched an app called eVigil to report any violation of its Model Code of Conduct, including hate speech and fake news. Further, it asked the leading social media platforms to silence political advertisements for 48 hours before the polls. It also directed social media companies to draft their own Code of Ethics for self-regulation.

Endnotes

One reason for the popularity of these services is that they are free and easy to access. However, as artist Richard Serra puts it,

If it’s free, you are the product.

Big Tech companies have enormous power, as is clear from the discussion so far. With time and an increasing user base, it only seems to be growing. It is easy to feel powerless in this situation at a personal level. However, at the end of the day, our data allows them to exert this enormous influence over society. We consent to give away all this data every time we go down a YouTube rabbit hole or start searching for products we will never buy on Amazon. This directly and negatively impacts our life. The recognition of this fact is essential to combat their stranglehold. There are various ways to stop being a slave of the algorithm. For example, you can use TrackMeNot to falsify search data. It requires a few uncomfortable hits and misses, but with determined resolve, it is possible to mitigate the problems significantly.

This article has been written by Akshita Rohatgi, an undergraduate student at the University School of Law and Legal Studies, GGSIPU, during her internship with The Cyber Blog India in January/February 2021.

Featured Image Credits: Background photo created by kjpargeter – www.freepik.com