Digital Evidence Law India and all about Anvar v Basheer case

Acquiring digital evidence is an extremely complex task because of the nature of digital evidence. If we looked at only one side of the coin, we would simply stick to that side given the forensics, technology and woohoo of acquiring evidence by forensics. Does this mean that we won only half the battle?

The law dealing with digital evidence varies from country to country. In India, the legislation that merged cyberspace technology and the law was the IT Act, of 2000 (amend. 2008). Yet the legislation holds a very minimal mention of digital evidence or even the type of cyber crimes that we see today. Indian law incorporated digital evidence into the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Digital evidence within the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Section 3 defines ‘all documents including electronic records produced for the inspection of the court’, as ‘documentary evidence’. Further, any other statement-related evidence is ‘oral evidence’. This section is relevant for digital evidence.

So what exactly is an ‘electronic record’?

Digital evidence within the IT Act, 2000

For this, let us look at Section 2(t) of the IT Act, 2000. It means ‘data, record or data generated, image or sound stored, received or sent in an electronic film or computer generated micro fiche.’

It is very easy to understand the meaning of data, record, image, sound and so on within the definition. A microfiche is a photographic film containing microimages.

Therefore, digital evidence can include anything from word documents to transaction logs, FTP logs of a server, GPS System tracks, computer memory, browser history and sorts of windows artefacts. (See here)

But, to recognize these records, we need to take a peek at Section 4 of the Act. It states that:

If any law requires information to be in written, typewritten or printed form, it can be :

- rendered and made available in an electric form, or;

- is accessible for subsequent reference.

Now, to further look into whether such evidence is admissible in Court, we must get back to the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Admissability of digital evidence under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Section 17 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 defines admission of evidence. In addition, Section 22-A provides for when any oral admission as to the content of the electronic record is relevant to the Court. Remember that until your evidence is admissible, none of the corroborations that you provide about its genuineness will be valid. After the test of admissibility, the biggest players in this scene are Sections 65-A and 65-B of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Digital evidence under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

While Section 65-A talks about how electronic records may be proved, It is to be read in accordance with the conditions under Section 65-B.

Section 65-B (1) states that any information—from the computer or device in question— whether printed on paper or stored, recorded or copied in optical or magnetic media shall be called a ‘document’. This is admissible in any proceeding when it serves as proof of the original information or even if it is direct evidence. But, such a document can act as a piece of admissible evidence only when it satisfies all the requisites under Section 65-B. That is why for investigators, evidence retention and preservation are important.

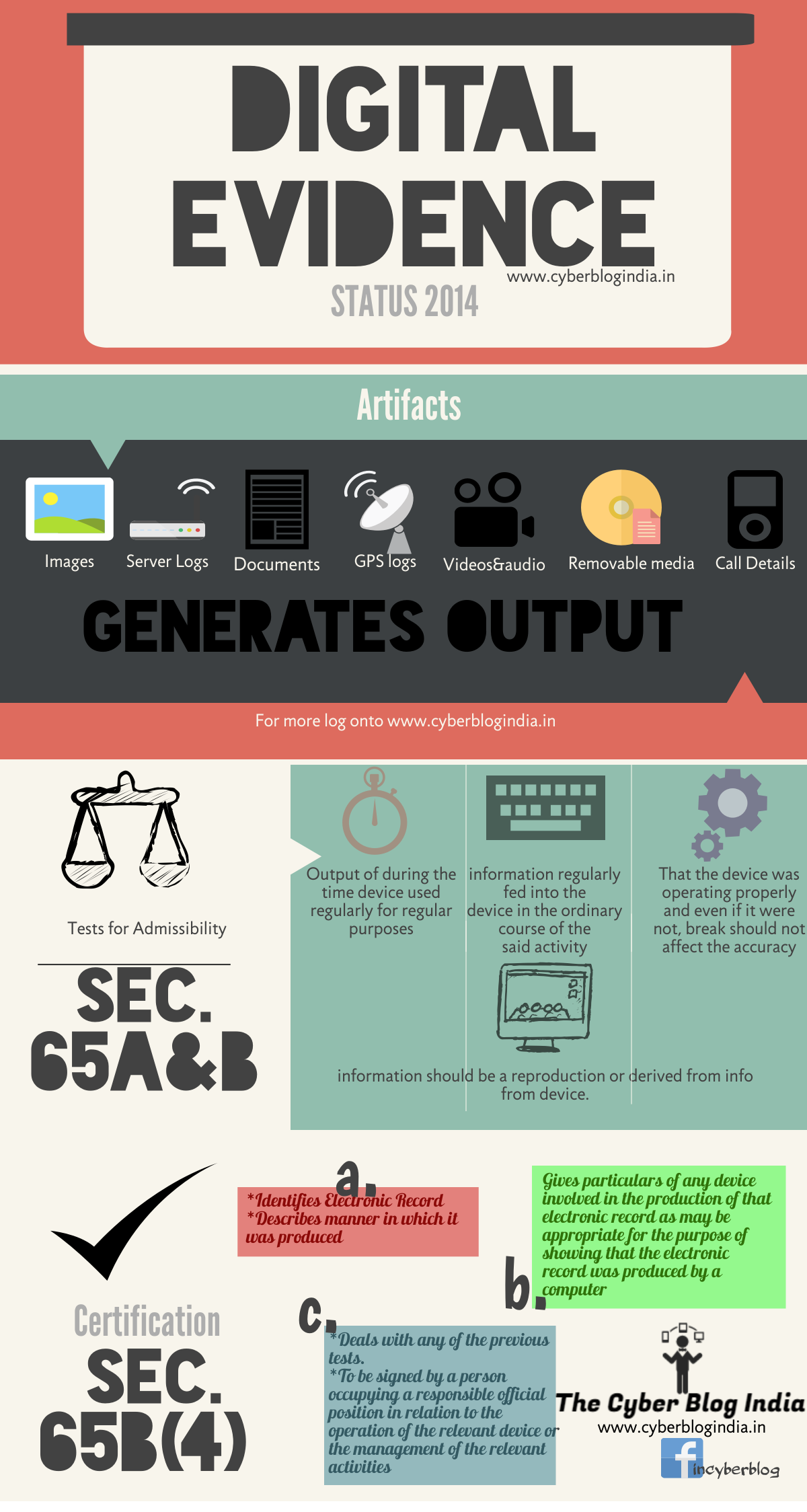

Section 65-B (2) lays down four prerequisites for the admissibility of a piece of digital evidence:

- Firstly, the computer output containing the information should have been produced by the computer. This act must have been done only during the period of using the computer to store or process information. Such regular use was only to any activities routinely carried out during the period. In addition, the person using the computer must have lawful control over the use of the computer.

- Secondly, it must be shown that during the said period, the information contained derived was ‘regularly fed into the computer in the ordinary course of the said activity’. Such information must be of the kind contained in the electronic record or the electronic record must be of the kind from which the information contained is derived.

- Thirdly, during the material part of the said period, the computer should have been operating properly. If it was not operating properly for some time, that break in time should not affect either the record or the accuracy of its contents.

- Lastly, the information contained in the record should be a reproduction of or derived from the information fed into the computer. And this must be in the ordinary course of the said activity. (Originally here)

Section 65-B (4) issues a certificate to identify the electronic record. This certificate describes the manner of producing the information contained. It gives the particulars of the device involved in the production of that record and deals with the conditions mentioned in Section 65-B (2). Finally, a person occupying a responsible official position (in relation to the operation of the relevant device) signs the certificate. This deems the electronic record to be evidence of the matter.

#DigitalEvidence Law in #India: https://t.co/UiSrF3RsKM#cyberlaw #cyberspace #evidence #hashing #theCBI #LEAs

— The Cyber Blog India (@incyberblog) February 20, 2016

All you need to know about Anvar v Basheer, the recent landmark case dealing with digital evidence

The state of affairs before the Anvar case

Before 2000, Electronically stored information was considered documentary evidence. This evidence was secondary in nature. These electronic ‘documents’ were cited as ‘printed reproductions’ or ‘transcripts’. Consequently, a competent signatory certified the authenticity of the documents. The signatory would then, identify her signature in court and be open to cross-examination. This simple procedure met the conditions of both Sections 63 and 65 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

The introduction of the Information Technology Act, 2000, amended section 59 of the Evidence Act. It excluded electronic records from the probative force of oral evidence, in the same manner as it excluded documents. Making an electronic record of oral evidence would amount to documentary hearsay evidence. Hence, this simply reapplied the documentary hearsay rule to electronic records.

In addition, the IT Act inserted two new evidentiary rules for electronic records in the Evidence Act: section 65-A and section 65-B. Therefore, electronic records were no longer secondary evidence under sections 63 and 65 of the act.

However, for a long time, the special law and procedure created by sections 65-A and 65-B of the Evidence Act did not apply to electronic evidence. This was disappointing since the cause of this non-use did not involve the law at all. India’s lower judiciary (trial courts) is vastly inept and technologically unsound. With exceptions for a few, trial judges simply do not know the technology the IT Act comprehends. It was, therefore, easier to carry on treating electronically stored information as documentary evidence.

This was the status quo that even the Supreme Court had upheld in the Parliament attacks case (State v Navjot Sandhu). It admitted the copies of call detail records without following procedures under Sections 65-A and 65-B.

How did the Anvar case change the current state of affairs?

In the Anvar case, the Supreme Court relied on two maxims —generalia specialibus non derogant (“the general does not detract from the specific”) and lex specialis derogat legi generali (“special law repeals general law”).

This meant that Sections 65-A and 65-B of the Evidence Act override the general law of documentary evidence. Therefore, for the Court to admit electronic evidence, the evidence had to satisfy all the requisites of section 65-B.

The view of the apex court thus disqualified oral evidence to attest to secondary documentary evidence. Nonetheless, only later, did there exist one belief that supported the disqualification. It was the fact that oral evidence under Section 22-A spoke about the genuineness of the evidence, not of the content given by an expert witness (under Section 45-A of the Act).

Now, the thumb rule to verifying evidence is by means of the specific laws of the Evidence Act.