The Ballot and the (Digital) Brainwash: Online Propaganda in the Electoral Process

The ballot is stronger than the bullet, as Lincoln has famously remarked. However, its strength is falling short in the face of brainwashing. These days, online electoral propaganda thwarts the legitimate transfer of power in democratic states. A study found that this online meddling impaired a shocking 88% of elections and referendums between June 2018 and May 2020. As the Internet’s reach expands, so does that of online electoral propaganda in a democracy.

Operation Disinformation

Merriam-Webster defines disinformation as

“false information deliberately and often covertly spread (as by the planting of rumours) in order to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.”

In our case, disinformation constitutes any online content knowingly manufactured or manipulated to affect the electoral process. Freedom House posits five essential techniques employed to manipulate online content:

- Propagandistic news,

- Fake news,

- Paid commentators,

- Bots, and

- Hijacking of real social media accounts.

Propagandistic and fake news is the Achilles’ heel of any democratic election. Examples are plenty. Fake news in the 2016 US Presidential elections chiefly favoured Trump over Clinton. Brazil’s 2018 and 2022 elections saw the rise of conspiracy theories and WhatsApp disinformation campaigns against Jair Bolsonaro’s primary opponent. Fake news during the 2018 Italian election aided the creation of Western Europe’s first populist government.

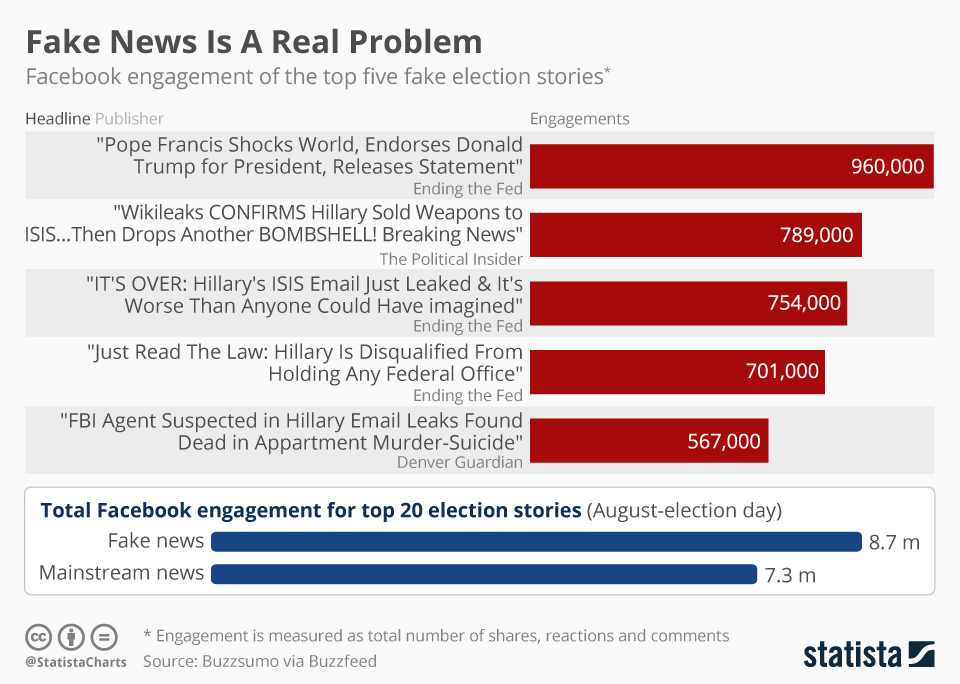

As for India, the 2019 Indian general elections had over 2 million supporters of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress (INC) sharing fake news. Fabricated news is ubiquitous during elections, but this is not the real problem. The issue is when most consumers find it credible and engage with it. In the 2016 US elections, for instance, fake news stories had more engagement on Facebook than mainstream news from August till the day of the election.

According to a Freedom House report, “keyboard armies” of political parties drive this fake news phenomenon. These armies comprise party-sponsored commentators, bots, and hijacked social media accounts. They manipulate online content inconspicuously. Party-sponsored commentators can be government staff, as in the case of Sudan and Vietnam. Consultancies and firms have previously undertaken the same in countries like Russia and Turkey. As for bots, it results in a megaphone effect when these bot accounts share a candidate’s message online and increase its reach. Bots can have a pronounced impact on elections, as seen in the 2016 US elections, where they discouraged voting by Black Americans.

Operation Restriction

Another key technique to subvert the electoral process is when the government restricts a variety of online content. Blocking access to the Internet or its websites during elections is one such restriction tool that countries employ. Really, African nations appear to have routinely exploited it—in 2021, Uganda became the 15th country in the continent since 2015 to censor the net during elections. Internet shutdowns or slowdowns in various parts of the country helped Yoweri Museveni secure a sixth term in the country’s presidential office.

Similarly, elections in Cambodia and Zimbabwe in 2018 involved the blocking of decisive websites that shared news and advocacy. In these cases, this blockage hinders the more extensive dissemination of election-related information that can sway voters. In other cases, governments have specifically and openly clamped down on opposition parties and activists that advance anti-government narratives during elections.

Not only do these restrictions undermine the legitimacy and transparency of democratic elections, but they also infringe on the human rights of citizens. When the Internet is curbed, fundamental rights like the right to freedom of speech and expression cannot be advanced, and such a right is most significant during an election. In fact, a joint declaration by some of the world’s central organisations (including the UN) has emphasised that

“cutting off access to the Internet, or parts of the Internet, for whole populations or segments of the public (shutting down the Internet) can never be justified”, and such a denial is “a punishment is an extreme measure”.

Governments also use legal tools to lodge electoral propaganda into online discourse. Countries like Turkey and India have arrested social media activists and users for anti-government posts before elections. Again, this hinders people’s right to freely express themselves online. It also encourages the misuse of laws, like the Digital Security Act in Bangladesh, to strengthen the government’s hold. Instead of providing rational digital security, governments use such acts to silence their opposition and alter the election procedures.

Conclusion

We must note that such digital propaganda builds on traditional means of spreading electoral propaganda –techniques like, say, the bandwagon effect (or persuading people to follow what the “majority” is thinking) have existed for a long time. What the Internet does is that it exacerbates these. For one, online propaganda is scattered. Even when a country blocks the Internet or legally obstructs opposition during elections, propaganda is congregated in one place. In contrast, the novel mix of bots and fake news is one big, chaotic mess that makes it hard to pin down the perpetrator. Additionally, the number of propagandists used to perform it is sizeable, given that it combines people, companies, and bots.

Such a complex network of disinformation travels quickly, can be engaged with by a more significant number of people, and employs tools like microtargeting (targeted online marketing that makes use of a user’s personal data to display tailored content) that are only possible because of the existence of the Internet. These characteristics have collectively made computational propaganda techniques a global phenomenon. Most of us know little about this sophisticated manipulation of our personal data and voting beliefs. As digital technologies become increasingly intrinsic to public affairs, we need to analyse how far-reaching their implications will be on the democratic nature of elections.

Featured Image Credits: Image by pch.vector on Freepik