Amway India Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. v. 1MG Technologies Pvt. Ltd. & Anr.

Amway India Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. v. 1MG Technologies Pvt. Ltd. & Anr.

(2019) 260 DLT 690 : (2019) 79 PTC 425

In the High Court of Delhi

CS (OS) 410, 453, 480, 531, 550/2018 and 75, 91/2019

Before Justice Prathiba M. Singh

Decided on July 08, 2023

Relevancy of the Case: Can e-commerce platforms allow the sale of products offered by direct selling entities without their consent?

Statutes and Provisions Involved

- The Direct Selling Guidelines, 2016 (Clause7(6))

- The Information Technology Act, 2000 (Section 79)

- The Legal Metrology Act, 2009

- The Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodity) Rules, 2011

- The Constitution of India, 1950 (Article 19(1)(g), 77)

- The Trade Marks Act, 1999 (Section 29, 30)

- The Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (Order VII Rule 11)

- The Prize Chits and Money Circulation Schemes (Banning) Act, 1978

Relevant Facts of the Case

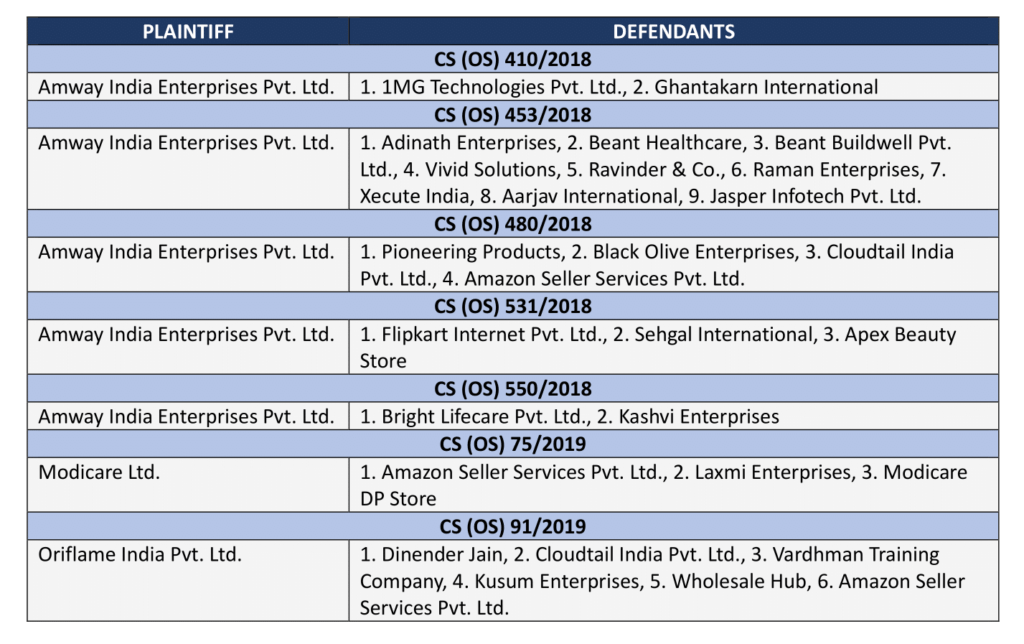

- In this judgement, the court has decided on a batch of seven suits filed by three plaintiffs. The following table lists the plaintiffs and defendants in these seven suits.

- Amway is one of the largest direct selling companies in the world. Their range of products includes manufacturing, marketing, and selling skin/health care products, nutrition, and supplements. They filed these suits seeking a perpetual and mandatory injunction restraining the defendants from indulging in unfair competitive practices.

- Amway sells its products through direct sellers under a Direct Seller’s Contract. The company also provides periodical training to these sellers, known as Amway Business Owners (ABO). Amway’s products are not available for sale legitimately through any e-commerce platform or mobile app.

- Amway had sent a cease and desist letter to e-commerce platforms to bring to their knowledge that third-party sellers were using Amway’s trademark without their consent. However, the e-commerce entities refused to comply with the Amway’s notice. They stated that they have safe harbour protection under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. Further, they only facilitate the transactions between the buyers and sellers. E-commerce platforms do not need authorisation from Amway as this is a seller’s responsibility.

- On April 09, 2018, FSSAI issued a letter addressing major e-commerce platforms to stop the sale of direct selling products without the consent of direct selling entities. E-commerce platforms neither challenged this order nor complied with it.

- Modicare is in the direct selling business, and its range of products includes health, skin, nutrition, cosmetics, personal care, home care, food, and beverages. The company offers a Customer Satisfaction Program, which gives its customers an irreversible 100% satisfaction or money-back guarantee.

- In June 2016, Modicare found its products available on Amazon without prior consent. On these product listings on Amazon, seller details were not available. Per their knowledge, defendants 2 and 3 in CS (OS) 75/2019 are not their authorised direct sellers.

- When Modicare reached out to Amazon, they took the defence under Section 79 and claimed protection as an intermediary.

- There are more than 700 products on Amazon bearing the mark Modicare. These products are available on Amazon at hefty discounts, resulting in declining sales of Modicare products through its direct selling network.

- In an earlier order on February 05, 2019, the court directed Amazon to provide seller details to Modicare. However, Amazon failed to provide the required details. Modicare moved a contempt application, followed by an unconditional apology by Amazon. The court had accepted this apology on March 14, 2019.

- Oriflame manufactures and sells cosmetics and wellness products through its network of direct sellers. In CS (OS) 91/2019, it claims that defendants number 1 to 5 are selling Oriflame products on Amazon without their authorisation.

- Upon receiving numerous complaints from its authorised direct sellers, it contacted Amazon and requested the removal of such products. However, Amazon denied all the allegations and claimed safe harbour protection under Section 79.

Prominent Arguments by the Advocates

Amway, in CS (OS) 410, 453, 480, 531, 550/2018:

- The counsel relied on the Direct Selling Guidelines issued by the Government of India in 2016. These guidelines regulate the direct selling business and are in the interest of consumers. As per clause 7(6), any person seeking to sell the products of a direct selling entity on an e-commerce platform must take prior consent. However, the defendant platforms enable the sale of Amway branded products without their consent.

- The products on these e-commerce platforms are available on a non-returnable basis. This is in stark contrast with Amway’s return policy. This would lead to the dilution of goodwill and reputation amongst its customers.

- The sale of Amway products through e-commerce and mobile apps is contrary to the approval granted by the Government of India in favour of Amway on August 04, 2004.

- The 2016 guidelines are binding in law. The persistent conduct of not taking down product listings after being duly informed shows that they are guilty of inducing a breach of contract. On almost all of the platforms, the sellers’ details are unavailable.

Modicare, in CS (OS) 75/2019:

- Amazon offers a large bundle of services for the use of its platform. This brings it out of the ambit of being an intermediary.

- Products listings on Amazon either do not mention MRP or display an inflated MRP. This contravenes the Legal Metrology Act, 2009 and the Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodity) Rules, 2011.

- Article 19(1)(g) does not apply in the context of the Direct Selling Guidelines. The e-commerce platforms cannot claim a fundamental right to sell the plaintiff’s products without their consent.

Oriflame, in CS (OS) 91/2019:

- For Amazon to claim protection under Section 79, it is under legal obligation to act on the notice sent by Oriflame. Simply claiming protection without performing due diligence is not enough.

- Oriflame products are available at inflated MRPs with heft discounts. This constitutes gross misrepresentation, leading to the duping of the consumer purchasing Oriflame products from Amazon.

Amazon, in CS (OS) 480/2018 and 75, 91/2019:

- Amazon is an intermediary under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. It provides a platform for thousands of buyers and sellers to transact on their platform. Even for the products manufactured by the plaintiff, third-party sellers have added the product listings. Products of the plaintiffs available on Amazon are genuine. Hence, the principle of exhaustion applies, and the plaintiffs cannot preclude sellers from selling their products through Amazon.

- For each seller, the platform generates a unique merchant ID. Sellers determine the maximum price and discount for each product.

- While there is a restriction on selling a product above MRP, there is no restriction on sale below the printed MRP. As a matter of policy, Amazon delists products from its platform when it comes to know that a product is being sold at a price higher than MRP. Further, it is the seller’s responsibility to ensure the accuracy of MRP.

- Amazon is not an active participant, and providing facilitation services does not remove the intermediary status. Amazon has no role in sourcing products, and the sellers retain the titles of their products. Section 79 requires content takedown upon receiving the actual knowledge. This actual knowledge has to be in the form of a court order.

- The counsel submitted that the Direct Selling Guidelines do not apply to Amazon and are not enforceable in law. Similarly, the FSSAI letter is neither binding nor applicable to Amazon.

- Moreover, it has an infringement/notice and takedown policy and a grievance redressal officer. The company has implemented this system to deal with intellectual property violations.

1MG Technologies, in CS (OS) 410/2018, and Bright Lifecare, in CS (OS) 550/2018:

- The counsel submitted that the Direct Selling Guidelines do not apply to e-commerce platforms. 1MG had forwarded one consumer complaint regarding the genuineness of the product to Amway. This shows the bonafide intention of 1MG. It is only because of 1MG’s actions that Amway learned about the sale of its products on 1MG’s platform. Amway has conveniently concealed this fact in its plaint.

- Section 30 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, protects 1MG and Bright Lifecare. The sale of genuine products does not constitute trademark infringement. The sellers’ details are easily accessible on their website.

- 1MG and Bright Lifecare are intermediaries. They comply with all the provisions of the Act and rules issued thereunder. They do not modify or alter any information in a product listing added by a seller. However, they are ready to assist the right owners as they must take down content upon receiving actual knowledge. Amway has to do the primary policing.

Flipkart, in CS(OS) 531/2018:

- Flipkart is a mere facilitator. For the product listing available on their platform, the sellers determine the prices of their goods. Therefore, it is only an intermediary and has safe harbour protection under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000.

- Direct Selling Guidelines only apply to direct selling entities and their authorised sellers. These guidelines do not apply to e-commerce platforms like Flipkart.

- When a seller adds a product, the platform confirms if they have the required authorisation to sell it.

Jasper Infotech, in CS(OS) 550/2018:

- Jasper Infotech operates the e-commerce platform Snapdeal. The counsel’s main defence was similar to that of Flipkart. Snapdeal has already appointed a Grievance Officer to deal with such grievances.

- This plaint is merely an attempt to protect the direct selling business model. Direct selling companies see this as a trade channel conflict.

Cloudtail India, in CS(OS) 480/2018 and 91/2019:

- Cloudtail is a seller on Amazon and provides quality products at affordable prices. It has a screening process in place that requires sellers to submit intellectual property registration and ownership documents. If not, it requires a vendor to provide warranties as to the genuineness of the products. It has a clear takedown policy, which relies on Amazon’s takedown policy.

- A vendor grants a royalty-free license to Cloudtail to sell and distribute their products. On this basis, Cloudtail was selling the plaintiffs’ products.

Beant Healthcare and Beant Buildwell, in CS(OS) 453/2018:

- The counsel prayed for the rejection of the plaint under Order VII Rule 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. This prayer is on the ground that Amway itself is selling its products online through its e-commerce website. A consumer can buy Amway products directly from the website without going to an authorised direct seller. Hence, Amway cannot preclude other parties from selling online.

Other sellers in the suits:

- Some sellers settled with the plaintiffs, gave undertakings, and returned the inventoried products to the respective plaintiffs.

- Other sellers have filed a written undertaking stating they have the necessary authorisation to sell the product. Some sellers have submitted that they obtained these products from authorised direct sellers of the plaintiff. However, none of the sellers filed any authorisation that permits them to sell on e-commerce platforms.

Stand of the Union of India:

- The purpose behind introducing the 2016 guidelines was to protect the consumers and the direct selling business. The Central Government called them an advisory so that the State Governments can make any required changes.

- The government has published the guidelines in the Official Gazette, per Article 77 of the Indian Constitution. So far, there is no pending challenge against their validity. Hence, these guidelines are valid and binding.

Opinion of the Bench

- The direct selling business has been prevalent in India. The Prize Chits and Money Circulation Schemes (Banning) Act, 1978 (“PCMCS Act”) fails to distinguish direct selling activities from Ponzi schemes or illegal money circulation schemes. The government formed an inter-ministerial committee to look into this issue. These efforts resulted in the introduction of the Direct Selling Guidelines, 2016. With the issuance of the gazette notification and subsequent adoption by states, it became binding executive instruction. Hence, the 2016 guidelines have the force of law.

- As per clause 7(6) of the guidelines, they apply to any person who seeks to sell a direct selling entity’s products. E-commerce platforms cannot claim their fundamental right to sell these products. They must obtain consent from a direct selling entity before listing or selling their products.

- If the court permits e-commerce platforms to violate the guidelines, direct selling entities will not have any recourse. Regulatory authorities and government entities have notified the defendants to comply with the guidelines. The defendants voluntarily chose to not comply with the requirements. They only challenged the legal nature and validity of the guidelines as a defence in the present suits.

- None of the e-commerce platforms can vouch that all the products on their platforms, being the plaintiffs’ marks, are genuine and authentic.

- The findings from all Local Commissioners’ Reports indicate a large-scale tampering of goods. For instance, Cloudtail could not trace the source of products to Amway. The sellers are tampering with the seals of the goods and resealing the products using thinners and glues. In the case of Amazon, the tampering was happening in its warehouse. This is entirely uncondonable.

- A review of existing policies of e-commerce platforms indicates that a seller cannot sell a product for which he is not authorised.

- The court also considered the US and European positions on this issue. The court relied on Heather R. Oberdorf v. Amazon.com Inc. to conclude that Amazon’s role is not just limited to intermediary. The court also mentioned two cases from Milan courts on this issue, namely Landoll S.r.l. v. MECS S.r.l. and L’Oreal Italia SPA v. IDS International Drugstore Italia SPA.

- Using a trademark in meta tags or advertising without the proprietor’s consent violates a trademark owner’s rights. As the defendants are using the plaintiffs’ names and marks to promote products, it would amount to infringement under Section 29 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999. Hence, the defendants cannot claim defence under Section 30.

- If an intermediary seeks to excuse itself from liability, it must fulfil the conditions in Section 79(2) of the Information Technology Act, 2000. Section 79 would only cover a party that merely hosts or links third-party data or information. Based on the information available on record, it is clear that the role of e-commerce entities is not merely of a passive intermediary. The platforms must fulfil due diligence requirements to enjoy safe harbour protection. Non-compliance with their own policies would take them out of the ambit of the safe harbour.

- E-commerce platforms are not merely passive non-interfering platforms. They provide a lot of value-added services to their users. Despite receiving notices from plaintiffs, their response was dismissive. The continued sale of the plaintiff’s products without their consent has resulted in the inducement of breach of contract. The e-commerce platforms have caused tortious interference in the contractual relationship of the plaintiffs with their distributors.

Final Decision

- The Direct Selling Guidelines, 2016, have the force of law and are binding.

- By an interim injunction order, the court restrained the defendants from advertising, displaying, and offering the plaintiffs’ products for sale on e-commerce platforms.